$\huge\text{Outline}$

- Computer Abstractions and Technology

- Instructions: Language of the Computer

- Arithmetic for Computers

Chapter 1 - Computer Abstractions and Technology

§1.1 Introduction

Classes of Computers:

- Personal computers

- Server computers

- Supercomputers

- Embedded computers

The Post-PC Era:

- Cloud computing

- Warehouse Scale Computers (WSC)

- Software as a Service (SaaS)

- Data centers

- Personal Mobile Device(PMD)

§1.2 Eight Great Ideas in Computer Architecture

Design for Moore’s Law

The number of transistors that can be integrated on a die would double every 18 to 24 months.

Gordon Moore, 1965

Use Abstraction to Simplify Design

High Level Language → (Compiler) → Assembly Code → (Assembler) → Machine Language → (Machine Interpretation) → Hardware Architecture Description → (Architecture Implementation) → Logic Circuit Description

Make the Common Case Fast

Performance via Parallelism

Performance via Pipelining

Performance via Prediction

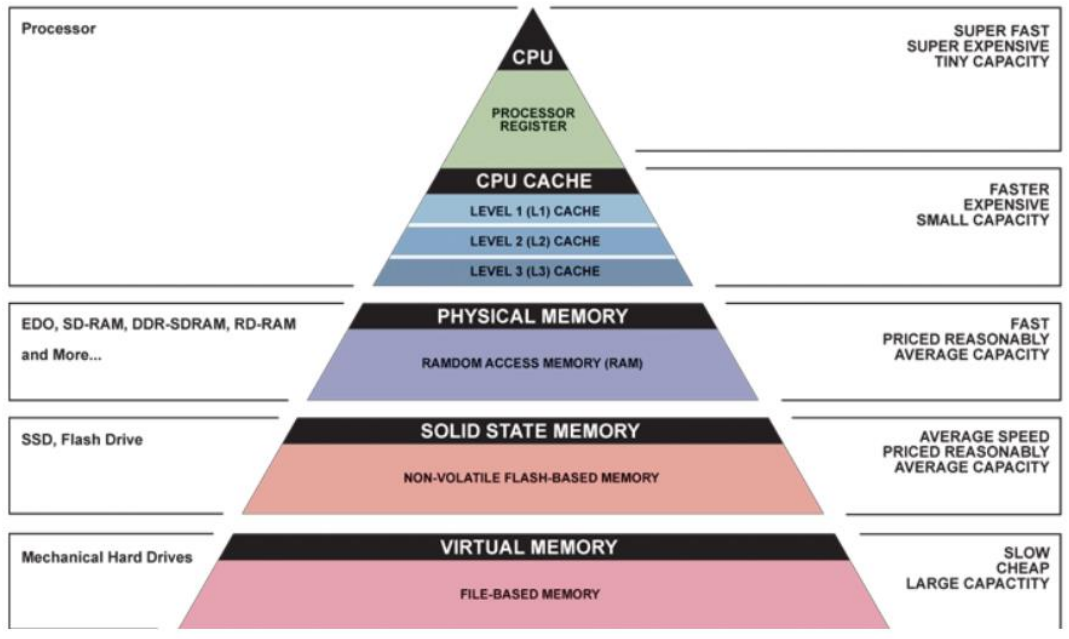

Hierarchy of Memories

Dependability via Redundancy

Redundancy so that a failing piece doesn’t make the whole system fail.

§1.3 Below Your Program

Between Your Program and Hardware:

- Application software

- Written in high-level language (HLL)

- System software

- Compiler: translates HLL code to machine code

- Operating System: service code

- Handling input/output

- Managing memory and storage

- Scheduling tasks & sharing resources

- Hardware

- Processor, memory, I/O controllers

Levels of Program Code:

- High-level language

- Level of abstraction closer to problem domain

- Provides for productivity and portability

- Assembly language

- Textual representation of instructions

- Hardware representation

- Binary digits (bits)

- Encoded instructions and data

§1.4 Under the Covers

Same components for all kinds of computer:

- I/O device

- Memory

- Processor

Inside the Processor:

- Datapath: performs operations on data

- Control: control the sequence of Datapath, memory, I/O

- Cache memory: Small fast SRAM memory for immediate access to data

§1.5 Technologies for Building Processors and Memory

(Different from textbook)

Processor Technology Trends:

- Shrinking of transistor sizes

- Transistor density increases by 35% per year and die size increases by 10-20% per year

- Transistor speed improves linearly with size

- Wire delays do not scale down at the same rate as transistor delays

Storage:

- Volatile main memory

- Loses instructions and data when power off

- Non-volatile secondary memory

- Magnetic disk

- Flash memory

- Optical disk (CDROM, DVD)

Memory and I/O Technology Trends:

- DRAM density increases by 40-60% per year, latency has reduced by 33% in 10 years (the memory wall!), bandwidth improves twice as fast as latency decreases.

- Disk density improves by 100% every year, latency improvement similar to DRAM.

- Networks: primary focus on bandwidth; 10Mb → 100Mb in 10 years; 100Mb → 1Gb in 5 years.

Power Consumption Trends:

$\text{Dyn Power} \propto \text{activity} \times \text{capacitance}\times \text{voltage}^2\times \text{frequency}$

Voltage & frequency are constant now. Capacitance per transistor is decreasing, number of transistors (activity) is increasing.

- Power leakage rising.

§1.6 Performance

$\text{*}$Focus on response time for now.

Execution Time:

- Elapsed time

- Total response time, including all aspects.

- Processing, I/O, OS overhead, idle time

- Determines system performance.

- Total response time, including all aspects.

- CPU time

- Time spent processing a given job

- Discounts I/O time, other jobs’ shares

- Comprises user CPU time and system CPU time

- Different programs are affected differently by CPU and system performance

- Time spent processing a given job

$\text{Performance}=1/\text{Execution time}$

Clock level:

$\text{CPU Time} = \text{Clock Cycles}\times\text{Clock Period}=\frac{\text{Clock Cycles}}{\text{Clock Rate}}$

Performance improved by:

- Clock cycles ↓

- Clock rate ↑

Trade off: rate vs. count

Instruction level:

$\text{Clock Cycles} = \sum\limits_{i=1}^n(\text{IC}_i\times \text{CPI}_i)$

$\text{CPU Time} = \text{IC} \times \text{CPI}\times \text{Clock Period}$

- Instruction Count for a program

- Determined by program, ISA and compiler

- Average cycles per instruction (CPI)

- Determined by CPU hardware

- If different instructions have different CPI

- Average CPI affected by instruction mix

The big picture:

$\text{CPU Time} = \frac{\text{Instructions}}{\text{Program}}\times \frac{\text{Clock Cycles}}{\text{Instruction}}\times \frac{\text{Seconds}}{\text{Clock Cycle}}=\text{IC}\times \text{CPI}\times \text{Tc}$

- Algorithm: affects IC, possibly CPI

- Programming language: affects IC, CPI

- Compiler: affects IC, CPI

- Instruction set architecture: affects IC, CPI, Tc

§1.7 The Power Wall

Energy Consumption of a chip:

- Energy consumption = dynamic energy + static energy

Energy for a single transistor switch: $E\propto \frac 1 2\times \text{Capacity load}\times \text{Voltage}^2$

Energy per second (Power): $\text{Power}\propto E\times \text{Frequency switched}$

The power wall:

- We can’t reduce voltage further: too leaky.

- We can’t remove more heat: too expensive.

§1.8 The Sea Change: The Switch from Uniprocessors to Multiprocessors

Uniprocessor Performance:

Constrained by power, instruction -level parallelism, memory latency

Multiprocessors:

- Multicore microprocessors

- More than one processor per chip

- Requires explicitly parallel programming

- Compare with instruction level parallelism

- Hardware executes multiple instructions at once

- Hidden from the programmer

- Hard to do

- Programming for performance

- Load balancing

- Optimizing communication and synchronization

- Compare with instruction level parallelism

§1.9 Real Stuff: Benchmarking the Intel Core i7

Standard Performance Evaluation Cooperative(SPEC) CPU Benchmark:

Develops benchmarks for CPU, I/O, Web, …

SPEC CPU2006:

Elapsed time to execute a selection of programs

- Negligible I/O, so focuses on CPU performance

Normalized relative to reference machine

Summarize as geometric mean of performance ratios

- CINT2006 (integer) and CFP2006 (floating-point)

$\sqrt[n]{\prod\limits_{i=1}^n \text{Execution time ratio}_i}$

| Instruction Count | CPI | Clock Cycle Time | Execution Time | Reference Time | SPEC ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $\text{IC}$ | $\text{CPI}$ | $\text{Tc}$ | $\text{T}_\text{Exe}$ | $\text{T}_\text{Ref}$ | $\frac{\text{T}_\text{Ref}}{\text{T}_\text{Exe}}$ |

SPEC Power Benchmark:

Power consumption of the server at different workload levels.

- Performance: ssj_ops (server side Java operations per second)

- Power: Watts

$\text{Overall ssj_ops per Watt} = (\sum\limits_{i=0}^{10}\text{ssj_ops}_i)/(\sum\limits_{i=0}^{10}\text{power}_i)$

§1.10 Fallacies and Pitfalls

Amdahl’s Law: performance improvements through an enhancement is limited by the fraction of time the enhancement comes into play.

- Corollary: make the common case fast

Fallacy: Computers at low utilization use little power (X)

Chapter 2 - Instructions: Language of the Computer

§2.1 Introduction

Concepts:

- Instructions, Instruction set

- Assembly language, Machine language

- Von Neumann Architecture

- Harvard Architecture

- reduced instruction set computer (RISC)

- complex instruction set computer (CISC)

Similarity of instruction set:

- base on similar design principles

- several basic operations provided

- designed for common goal

Design target:

- easy to build

- maximizing performance and minimizing cost and energy

Important design principles:

- keep the hardware simple

- keep the instructions regular

Design Principles

- Simplicity favors regularity

- Regularity makes implementation simpler

- Simplicity enables higher performance at lower cost

- Smaller is faster

- Register vs. memory

- Number of registers is small

- Make the common case fast

- Small constants are common

- Immediate operand avoids a load instruction

- Good design demands good compromises

- Different formats complicate decoding, but allow 32-bit instructions uniformly

- Keep formats as similar as possible

§2.2 Operands

Registers:

- MIPS ISA: 32 registers.

- Reason for the limit of 32 registers: Smaller is faster

- MIPS: Each register is 32-bit wide, a word.

Memory Operands:

- Values must be fetched from memory

- load word:

lw \$t0, memory-address - store word:

sw \$t0, memory-address

Memory Address:

The compiler organizes data in memory… it knows the location of every variable (saved in a table)… it can fill in the appropriate mem-address for load-store instructions.

Immediate Operands:

An immediate instruction uses a constant number as one of the inputs (instead of a register operand).

Registers vs. Memory:

- Registers are faster to access than memory

- Operating on memory data requires loads and stores

- More instructions to be executed

- Compiler must use registers for variables as much as possible

- Only spill to memory for less frequently used variables

- Register optimization is important!

§2.3 Numeric Representations

Decimal, Binary, Hexadecimal

Unsigned Binary Integers:

$x=x_{n-1}2^{n-1}+x_{n-2}2^{n-2}+\cdots + x_12^1+x_02^0, x\in[0,2^n-1]$

2s-Complement Signed Integers:

$x=-x_{n-1}2^{n-1}+x_{n-2}2^{n-2}+\cdots + x_12^1+x_02^0, x\in[-2^{n-1},2^{n-1}-1]$

Signed Negation:

2’s complement = 1’s complement + 1

Sign Extension:

Representing a number using more bits, and preserve the numeric value.

Replicate the sign bit to the left.

addi, lb, lh, beq, bne

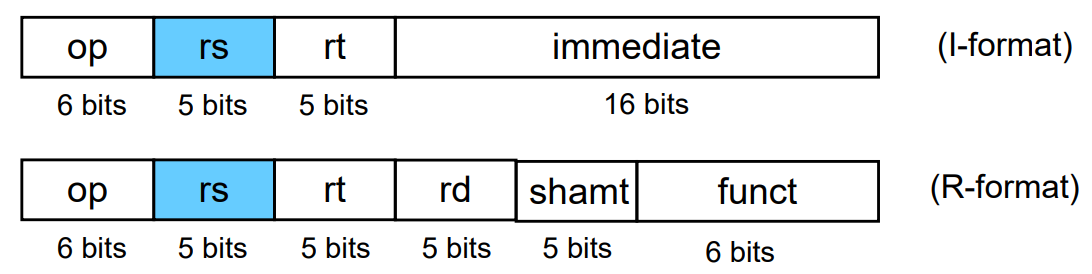

Instruction Formats

§2.4 Instructions

Arithmetic instruction: add, sub, …

Data transfer instruction: lw, sw, lh, sh, …

Logical instruction: and, or, …

Conditional branch: beq, bne, slt, …

§2.5 Instruction Formats

Registers:

| Name | Number | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| $zero | 0 | Constant value 0 |

| $at | 1 | Assembler Temporary |

| $v0-$v1 | 2-3 | Values for Function Results and Expression Evaluation |

| $a0-$a3 | 4-7 | Arguments |

| $t0-$t7 | 8-15 | Temporaries |

| $s0-$s7 | 16-23 | Saved Temporaries |

| $t8-$t9 | 24-25 | Tempoaries |

| $gp | 28 | Global Pointer |

| $sp | 29 | Stack Pointer |

| $fp | 30 | Frame Pointer |

| $ra | 31 | Return Address |

R-type instruction:

| opcode | source 1 | source 2 | dest | shift amt | function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| op | rs | rt | rd | shamt | funct |

| 6 bits | 5 bits | 5 bits | 5 bits | 5 bits | 6 bits |

I-type instruction:

| opcode | source | dest | constant |

|---|---|---|---|

| op | rs | rt | const |

| 6 bits | 5 bits | 5 bits | 16 bits |

J-type instruction:

| opcode | target address |

|---|---|

| 6 bits | 26 bits |

§2.6 Procedures

Procedure lifespan:

- acquires resources

- performs task

- covers its tracks

- returns back with desired result

Steps of procedure execution (caller calls the callee):

- parameters (arguments) are placed where the callee can see them

- control is transferred to the callee

- acquire storage resources for callee

- execute the procedure

- place result value where caller can access it

- return control to caller

Registers Used during Procedure Calling:

- The registers are used to hold data between the caller and the callee:

- $a0 - $a3: four argument registers to pass parameters

- $v0 - $v1: two value registers to return the values

- $ra: one return address register to return to the point of origin in the caller

Storage Management on a Call/Return:

- A new procedure must create space for all its variables on the stack

- Before executing the jal, the caller must save relevant values in $s0-$s7, $a0-$a3, $ra, temps into its own stack space

- Arguments are copied into $a0-$a3; the jal is executed

- After the callee creates stack space, it updates the value of $sp

- Once the callee finishes, it copies the return value into $v0, frees up stack space, and $sp is incremented

- On return, the caller may bring in its stack values, $ra, temps into registers

Updating $sp can be ahead of save caller-saved registers, e.g. MIPS clang 16.0.0. It is reasonable in the sense that the stack space should be allocated before being used. (Supplement from NeumoNeumo)

Saving Conventions:

- Caller saved: $t0-$t9, $ra, $a0-$a3

- Callee saved: $s0-$s7

Memory Layout:

- Text: program code

- Static data: global variables

- static variables in C, constant arrays and strings

- $gp initialized to address allowing ±offsets into this segment

- Dynamic data: heap

- malloc in C, new in Java

- Stack: automatic storage

Local Data on the Stack:

Local data allocated by callee

- C automatic variables

Procedure frame (activation record)

- Used by some compilers to manage stack storage

In

cpython(commit 95ee7c), the function runtime is stored inPyFrameObjectwhich is allocated on the heap. (Acceleration of function calls in python 1.11 is due in large part to the optimization of memory allocation for PyFrameObject)

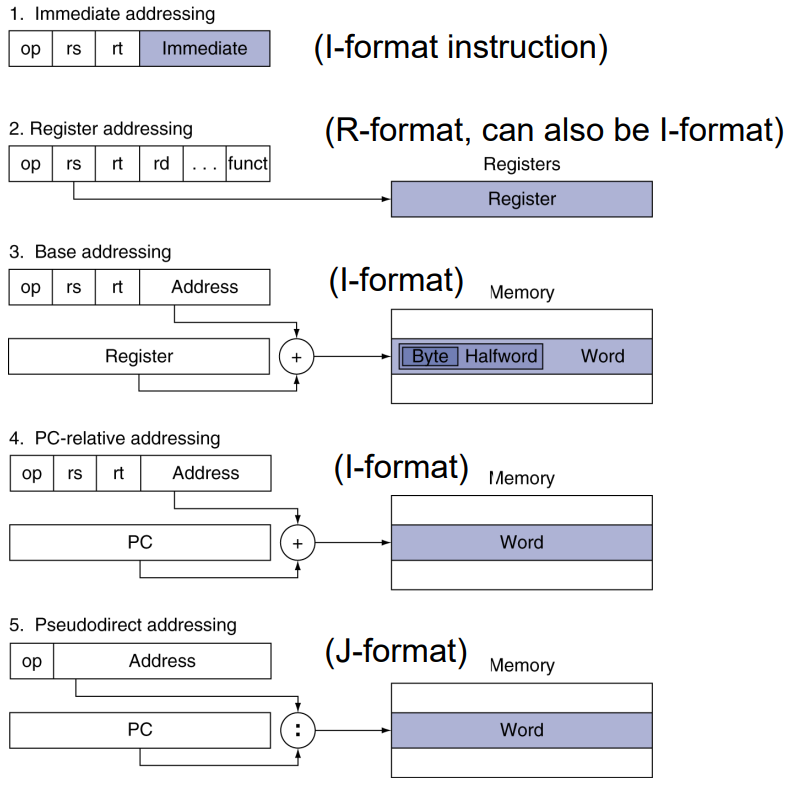

§2.7 Addressing

Immediate Addressing:

addi, subi, andi, ori...

$\text{hi = x>>16}$, $\text{lo=x-(hi<<16)}$

lui + ori = 32-bit constant

Register Addressing:

and, andi, sub, subi, lw...

Using register as the operand.

Base/displacement Addressing:

lw, sw, lh, sh, lb, sb...

The address is the sum of a register and a constant.

Branch Addressing (PC-relative addressing):

beq, bne

$\text{Target address = PC + 4 + constant × 4}$

Jump Addressing (Pseudo-direct addressing):

j, jal

$\text{Target address = PC[31:28]:(address×4)}$

Address times 4 because it is the “word address”.

If branch target is too far to encode with 16-bit offset, assembler rewrites the code to “double jump”.

§2.8 Translating and Starting a Program

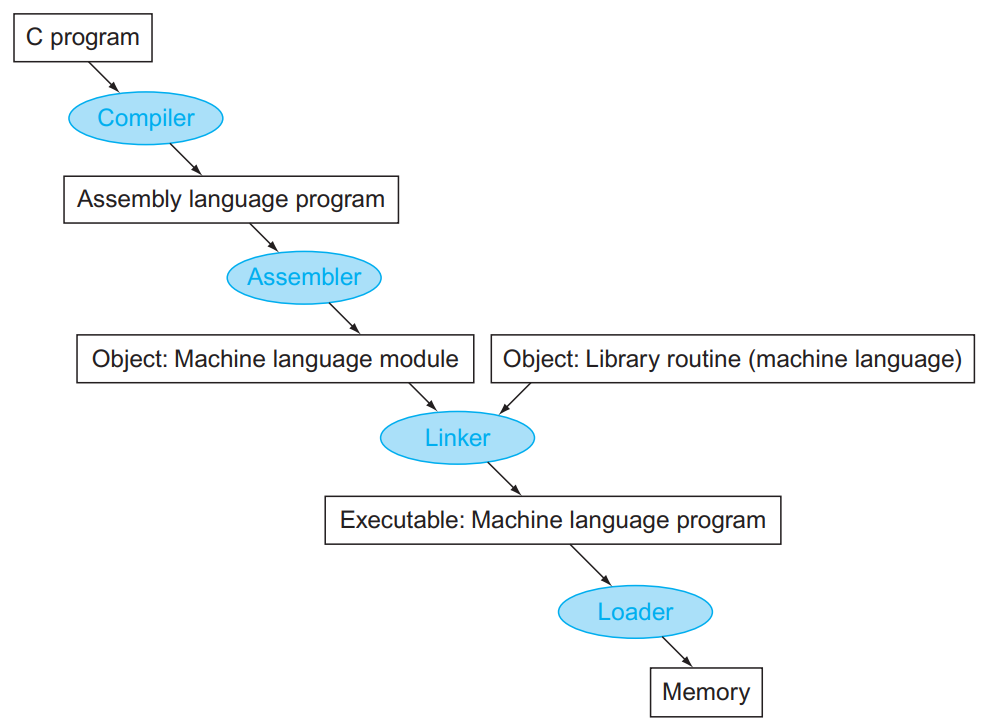

A translation hierarchy for C:

Role of Assembler:

- pseudo-instructions → actual hardware instructions

- assembly instructions → machine instructions

Role of Linker:

- Stitches different object files into a single executable

- patch internal and external references

- determine addresses of data and instruction labels

- organize code and data modules in memory

- Dynamically linked libraries – the executable points to dummy routines – these dummy routines call the dynamic linker-loader so they can update the executable to jump to the correct routine.

Linker Simulation:

- Combine the

Text sizeandData size. - Determine the order of objects.

- Combine the text segment, conventionally start from $0040\ 0000_\text{HEX}$.

- Modify the jump address according to new text addresses.

- Combine the data segment, conventionally start from $1000\ 0000_\text{HEX}$.

- Modify the memory operations according to new data addresses. Be careful about the sign extension!

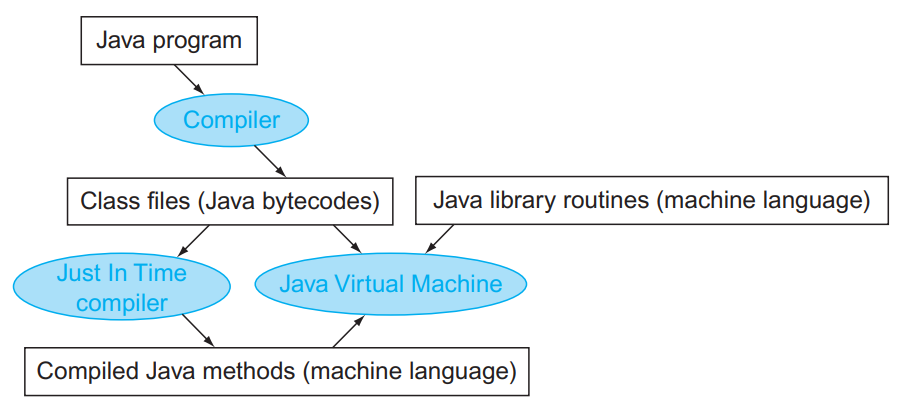

A translation hierarchy for Java:

§2.9 RISC-V

Differences between MIPS32 and RISC-V32:

| MIPS32 | RISC-V32 | |

|---|---|---|

| License | Proprietary | Open-Source |

| Endianness | Big-endian | Little-endian |

| Addressing modes | 5 | 4 |

| Conditional branches | slt, sltu + beq, bnq | +blt,bge,bltu,bgeu |

RISC-V Registers:

| Name | Usage |

|---|---|

| x0 | the constant value 0 |

| x1 | return address |

| x2 | stack pointer |

| x3 | global pointer |

| x4 | thread pointer |

| x5-x7 | temporaries |

| x8 | frame pointer |

| x9 | saved registers |

| x10-x11 | function arguments/results |

| x12-x17 | function arguments |

| x18-x27 | saved registers |

| x28-x31 | temporaries |

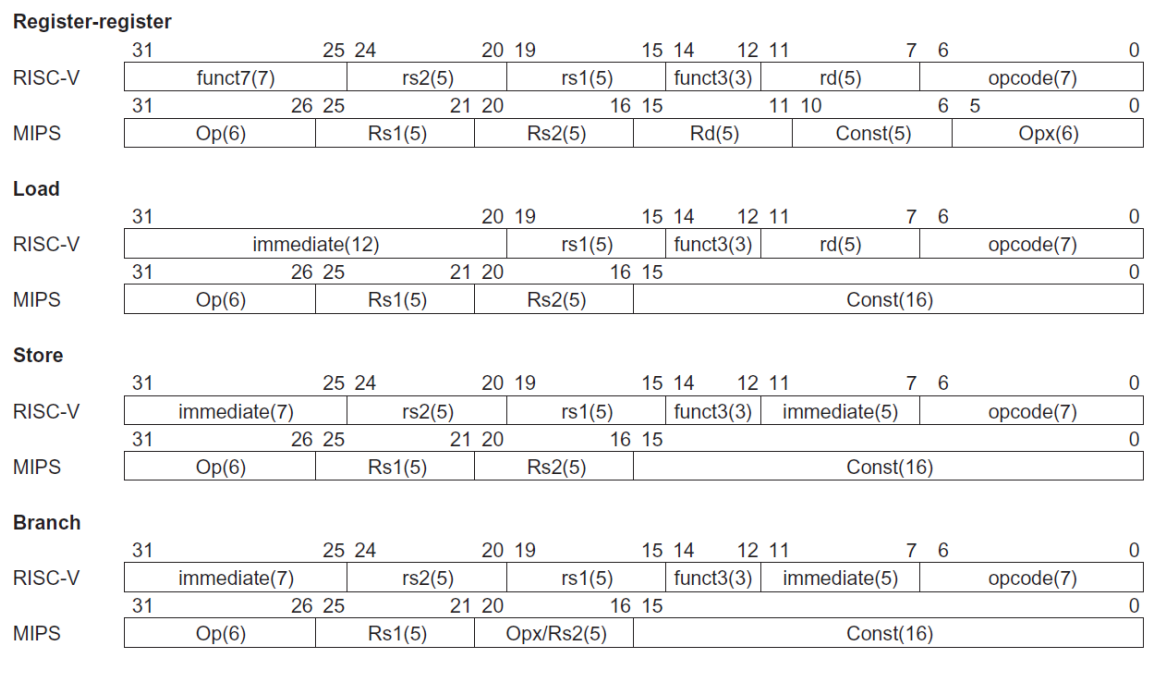

R-type instruction:

Arithmetic instruction format.add, xor

| funct7 | rs2 | rs1 | funct3 | rd | op |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 bits | 5 bits | 5 bits | 3 bits | 5 bits | 7 bits |

I-type instruction:

Loads & immediate arithmetic.addi, lw

| immediate[11:0] | rs1 | funct3 | rd | op |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 bits | 5 bits | 3 bits | 5 bits | 7 bits |

S-type instruction:

Stores.sw, sb

| immed[11:5] | rs2 | rs1 | funct3 | imme[4:0] | op |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 bits | 5 bits | 5 bits | 3 bits | 5 bits | 7 bits |

SB-type instruction:

Conditional branch format.beq, bge

| immed[12,10:5] | rs2 | rs1 | funct3 | imme[4:1,11] | op |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 bits | 5 bits | 5 bits | 3 bits | 5 bits | 7 bits |

UJ-type instruction:

Unconditional jump format.jal

| immediate[20,10:1,11,19:12] | rd | op | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17 bits | 3 bits | 5 bits | 7 bits |

U-type instruction:

Upper immediate format.lui

| immediate[31:12] | rd | op | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17 bits | 3 bits | 5 bits | 7 bits |

MIPS & RISC-V Instruction Formats:

§2.10 More ISAs

ARM v8, Intel x86

Chapter 3 - Arithmetic for Computers

§3.1 Addition and Subtraction

Integer Overflow:

add( + , + ) = -add( - , - ) = +sub( + , - ) = -sub( - , + ) = +

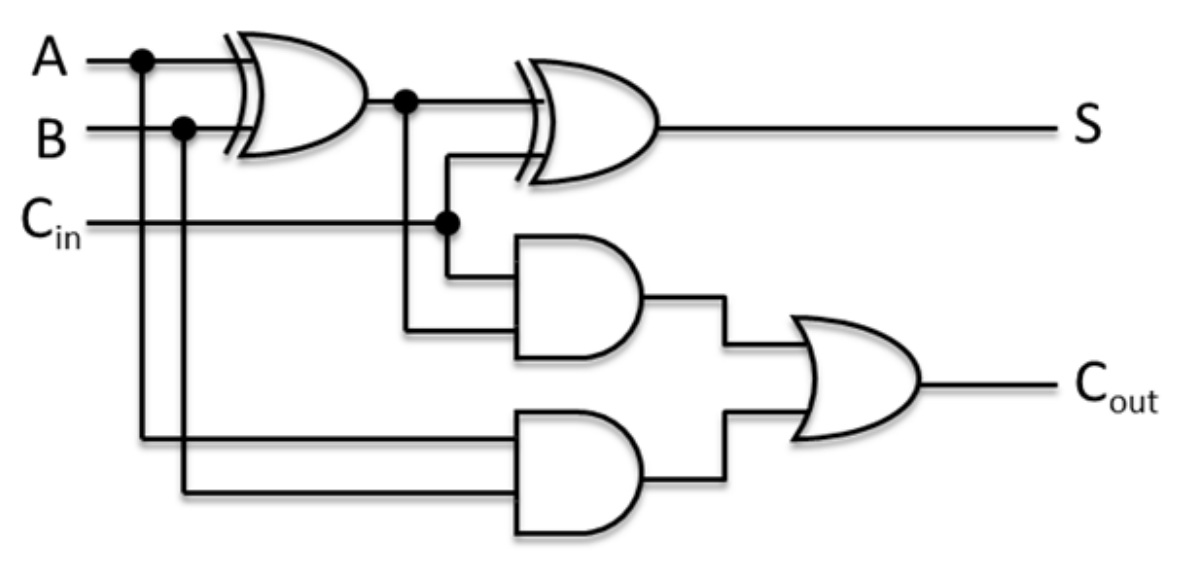

1-bit Adder:

1-bit ALU and 32-bit ALU:

- If op = 0, o = a & b (and)

- If op = 1, o = a | b (or)

- If op = 2, o = a + b (add)

To obtain 32-bit ALU, sequentially connect the 1-bit ALU via Carry, bind op to the same operation.

Dealing with Overflow:

- Use unsigned operations.

- On overflow, raise exceptions:

- Save

pcin exception program counterepc. - Jump to predefined handler address.

mfc0(move from coprocessor reg) instruction can retrieve EPC value, to return after corrective action.

- Save

- Saturating operations:

- On overflow, result is largest representable value.

SIMD: Single-instruction, multiple-data. See CS205 C/C++ Lecture 8: Speedup Your Program (^^ ;

§3.2 Multiplication

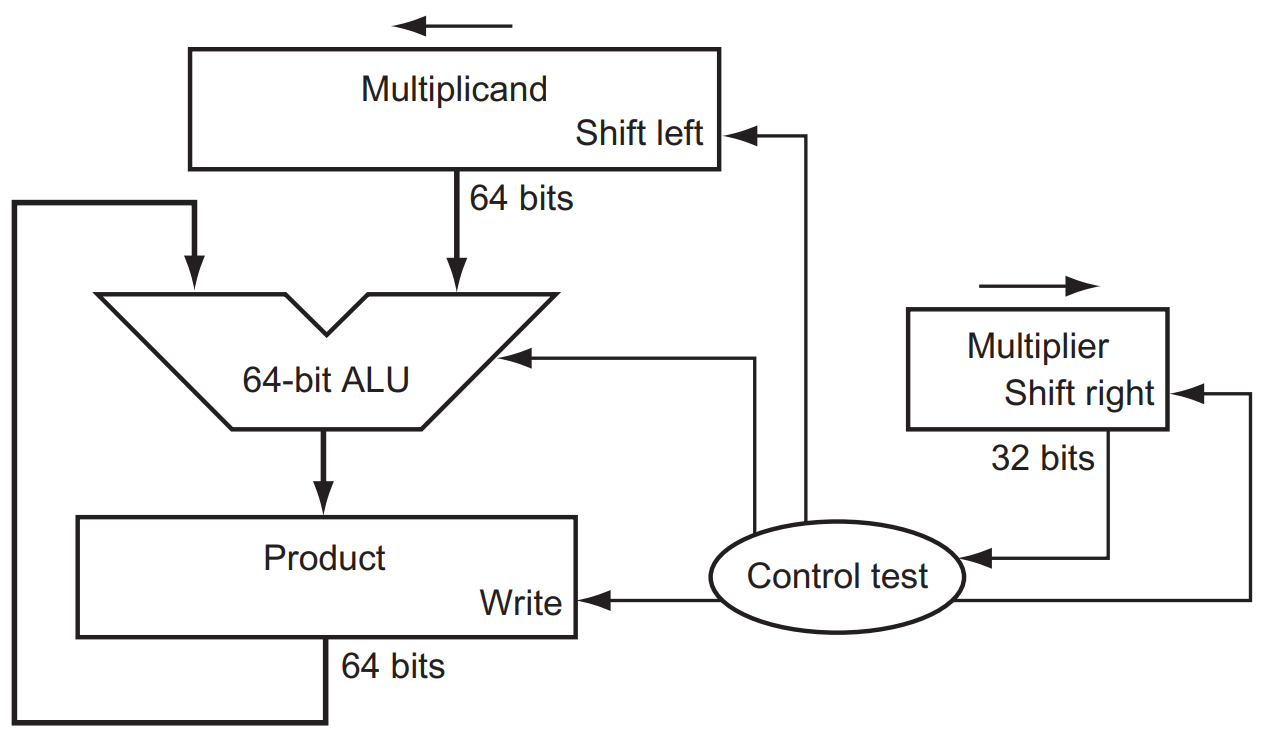

Naive version:

If the least significant bit of the multiplier is 1, add the multiplicand to the product. If not, go to the next step. Shift the multiplicand left and the multiplier right in the next two steps. These three steps are repeated 32 times.

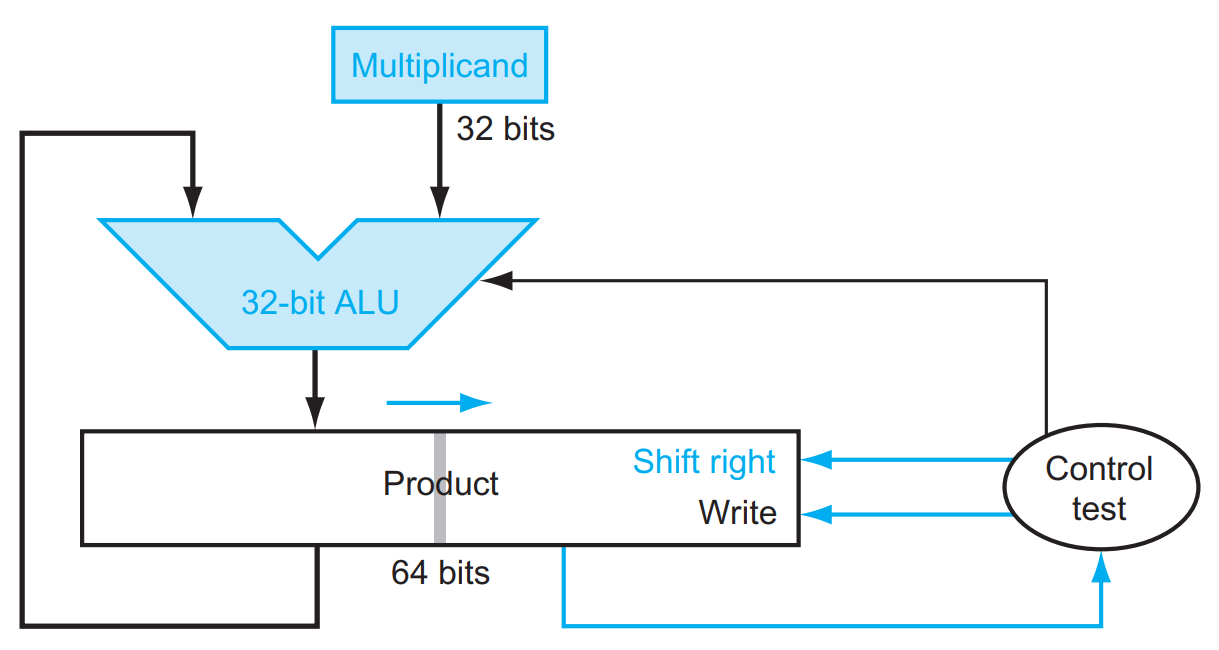

Refined version:

The Multiplicand register, ALU, and Multiplier register are all 32 bits wide, with only the Product register left at 64 bits.

Now the product is shifted right. The separate Multiplier register also disappeared. The multiplier is placed instead in the right half of the Product register.

Signed Multiplication:

Faster Multiplication:

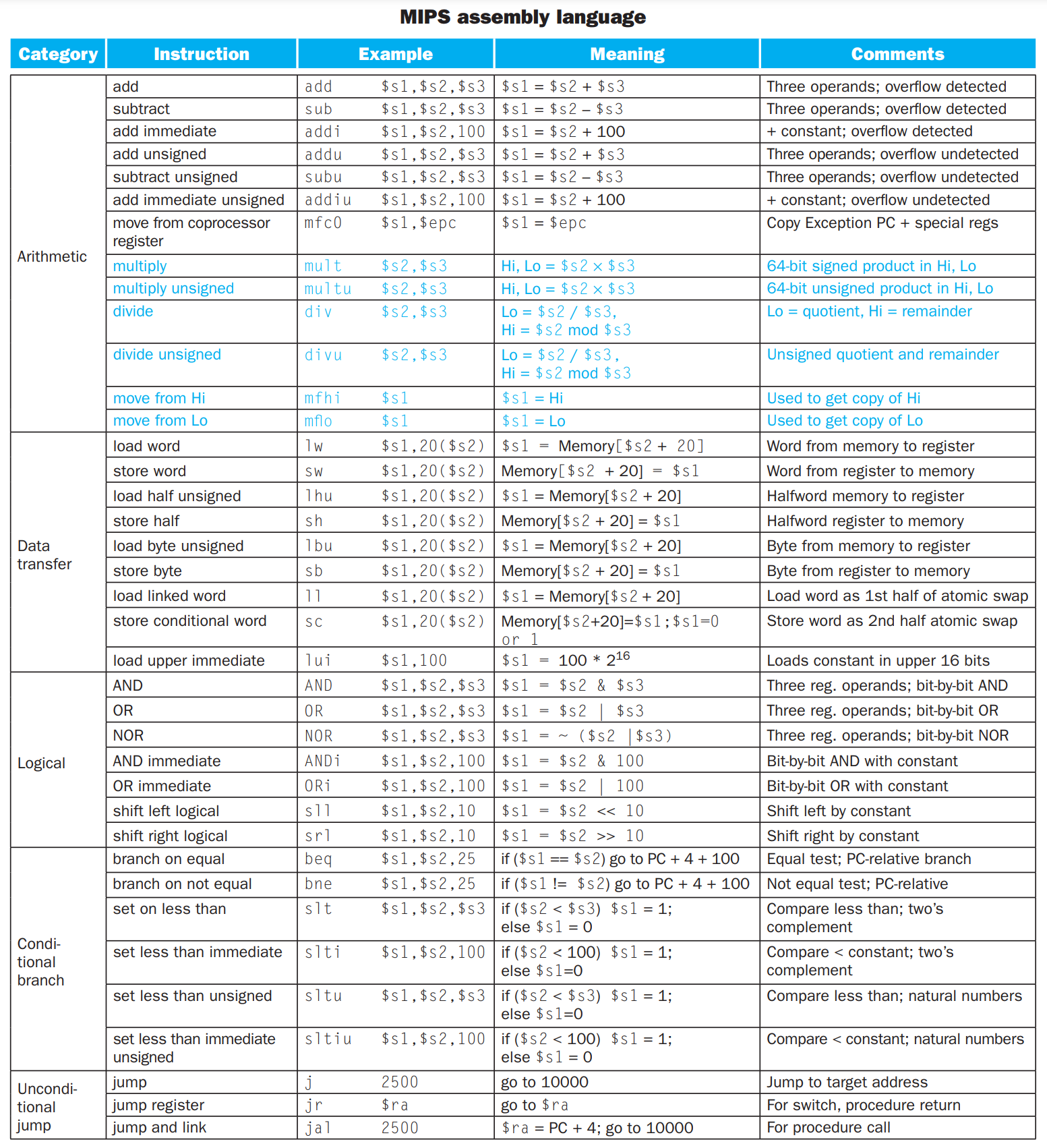

Appendix

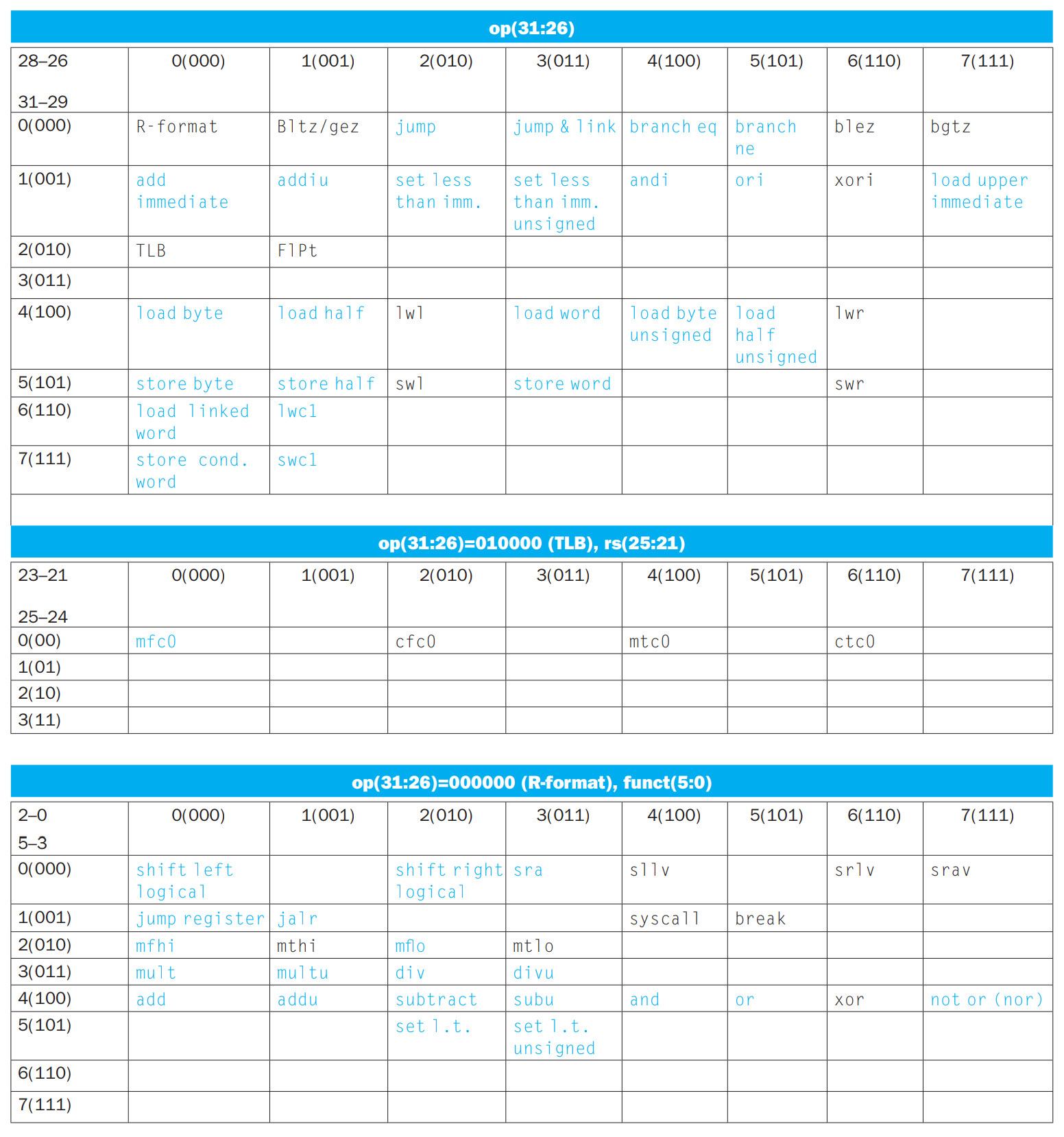

MIPS Core Architecture

MIPS instruction encoding